Photo by Brian McGowan

Unless we do something proactively, social engineering’s impact is expected to keep getting worse as people’s reliance on technology increases and as more of us are forced to work from home.

Contact tracing, superspreaders, flattening the curve — concepts that in the past were the domain of public health experts are now familiar to people the world over. These terms also help us understand another virus, one that is endemic to the virtual world: social engineering that come in the form of spear-phishing, pretexting, and fake-news campaigns.

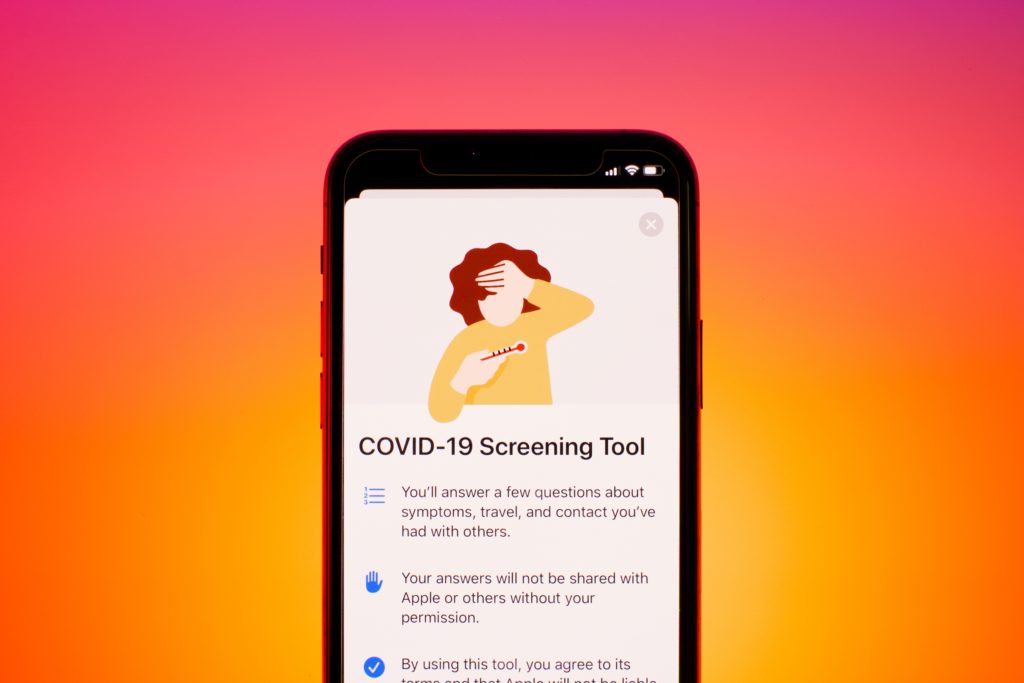

As quickly as the coronavirus began its spread, news reports cautioned users of social engineering attacks that tout fake cures and contact-tracing apps. This was no accident. In fact, there are a number of parallels between the human transmission of COVID-19 and social engineering outbreaks:

- Just like coronavirus transmits from person to person through respiratory droplets, social engineering also passes from users through infected computing devices to other users. Because of this transmission similarity, just as infected people, by virtue of their physical proximity to many others, act as superspreaders for COVID-19, some technology users act likewise. These tend to be people with many virtual friends or those subscribing to many online services who consequently have a hard time discerning a real notification or communication from one of these personas or services from a fake one. Such users are prime targets for social engineers looking for a victim who can provide a foothold into an organization’s computing networks.

- The vast majority of people infected with this coronavirus have mild to moderate symptoms. The same is the case with most victims of social engineering because hackers usually lurk imperceptibly as they make their way through corporate networks. They often go undetected for months — on average, at least 101 days— showing no signs or symptoms.

Just as no one has immunity from COVID-19, no one is immune against social engineering. By now everyone, all over the world, has been targeted by social engineers, and many — trained users, IT professionals, cybersecurity experts, and CEOs — have fallen victim to a spear-phishing attack.

Just as no one has immunity from COVID-19, no one is immune against social engineering. By now everyone, all over the world, has been targeted by social engineers, and many — trained users, IT professionals, cybersecurity experts, and CEOs — have fallen victim to a spear-phishing attack.- COIVD 19’s outcomes are worse for people who have prior health conditions and for people who are older. Similarly, the outcomes of social engineering are worse for users with poor computing habits and poor technical capabilities. Many of these tend to be senior citizens and retired individuals who lack updated operating systems, patches that protect them from infiltration, and access to managed security services.

- Finally, personal hygiene — hand washing, use of masks, social isolation — is the primary protection against coronavirus infection. Likewise, for protecting against social engineering, digital hygiene — protecting devices, keeping updated virus protections and patches, and being careful when online — is the only protection that everyone from the FBI to INTERPOL has in their arsenal.

But beyond these similarities, social engineering outbreaks are actually harder to control than coronavirus infections:

1. Social engineering infections pass through devices wirelessly, making it hard to contact-trace infection sources, isolate machines, and contain them.

2. There are well-established scientific processes that the medical community has developed to identify knowledge gaps about coronavirus. This helps researchers focus. In contrast, even the fundamentals of social engineering — such as when it’s correct to call an attack a breach or a hack — lacks clarity. It’s hard to do research in an area when there is no consensus on what the problem should be called or where it begins and ends.

3. While human hygiene is well researched, digital hygiene practices aren’t. For instance, in 2003, NIST developed password hygiene guidelines asking that all passwords contain letters and special characters and are changed every 90-days. The guideline was developed studying how computers guessed passwords, not how humans remembered them. Consequently, users the world over reused passwords, wrote them down on paper to aid their memory, or blindly entered them on phishing emails that mimicked various password-reset emails — until 2017, when these problems were recognized and the policy was reversed.

3. While human hygiene is well researched, digital hygiene practices aren’t. For instance, in 2003, NIST developed password hygiene guidelines asking that all passwords contain letters and special characters and are changed every 90-days. The guideline was developed studying how computers guessed passwords, not how humans remembered them. Consequently, users the world over reused passwords, wrote them down on paper to aid their memory, or blindly entered them on phishing emails that mimicked various password-reset emails — until 2017, when these problems were recognized and the policy was reversed.

4. Evidence points to those who have recovered from coronavirus having at least short-term immunity to it. In contrast, organizations that have had at least one significant social engineering attack tend to be attacked again within the year. Because hackers learn from every attack, this suggests that the odds of being breached by social engineering actually increase with each subsequent attack.

5. Our response to COVID-19 is informed by reporting throughout the healthcare system. Unfortunately, there is no similar reporting mechanism for social engineering. For this reason, a hacker can conduct an attack in one city and replicate it in an adjoining city, all using the same malware that could have easily been defended against had someone notified others. We saw this trend play out in ransomware attacks that crippled computing systems in Louisiana’s Vernon Parish in November 2019, quickly followed by six other parishes, and continuing through the rest of the state in February 2020.

Because of these factors, the economic impact of social engineering continues to grow. There has been a 67% increase in security breaches in the past five years, and last year companies were expected to spend $110 billion globally to protect against it. This makes social engineering one of the biggest threats to the worldwide economy outside of natural disasters and pandemics.

Because of these factors, the economic impact of social engineering continues to grow. There has been a 67% increase in security breaches in the past five years, and last year companies were expected to spend $110 billion globally to protect against it. This makes social engineering one of the biggest threats to the worldwide economy outside of natural disasters and pandemics.

Just as we are fighting the pandemic, we must coordinate our efforts to combat social engineering. Without it, there will be no vaccine or cure. To this end, we must develop intraorganizational reporting portals and early-warning systems to warn other organizations of breaches. We also need federal funding for basic research on the science of cybersecurity along with the development of evidence-based digital hygiene initiatives that provide best practices that take into account the user and their use cases. Finally, we must enlist social media platforms for tracing the superspreaders in their users, and develop open source awareness and training initiatives to protect them and the cyber-vulnerable from future attacks.

Unless we do something proactively, social engineering’s impact is expected to keep getting worse as people’s reliance on technology increases and as more of us are forced to work from home, away from the protected IT enclaves of organizations. We may in the end win the fight against the coronavirus, but the war against social engineering has yet to begin.

*A version of this piece appeared in Dark Reading: https://www.darkreading.com/endpoint/what-covid-19-teaches-us-about-social-engineering/a/d-id/1337979